Fencer, or the art of “getting off on the right foot”

" The clock doesn't influence, it directs ." This phrase, spoken without emphasis by Alex Fava, sums up a life he has so far dedicated to fencing. Being a top-level athlete, it seems, means spending one's life coexisting with time, taming it, trying to bend it to one's will, until it inevitably reasserts its rights, as always.

Montpellier, 1994. Alex Fava was six years old when he first donned a fencing mask. He is now thirty-six, hung up his boots and retired from the sport last year. In the meantime, he has experienced victories and failures, injuries and podiums, and now he is devoting himself to "what comes next," as they say in the jargon. Thirty years spent crossing swords with a merciless discipline in a career he himself describes as classic: his first steps as a fencer in a club in Montpellier, then several years at the Reims training center, the French youth team, and finally INSEP (the National Institute of Sport, Expertise, and Performance) for thirteen seasons. To his credit, six French championship titles, European medals, and the best of all, a world title with a team gold medal at the World Championships in Cairo in 2022. A consecration!

Alex Fava was never " the favorite, the great fencing talent who was destined for a great career ," he says. "I always had to work hard and develop mental strength in terms of self-denial, rebounding, and questioning myself ." While he wasn't the favorite, he was an excellent endurance athlete. "I went into it blindly. I didn't even know at the beginning if I was going to have a career and how long it would last. The hardest part isn't achieving a performance, but being consistent in it. I always kept going, telling myself that everything could end overnight, " he says. His words perfectly sum up the strange relationship that high-level athletes have with time: always projected toward the future, never certain of what will follow. Moving forward without guarantees or a safety net, and sometimes even without memory either. " I have very few extremely precise memories of my competitions. It's strange." The strong sensations remain, but not the actions and touches. During a match, we are so focused on the present that it is difficult to remember exactly what happened afterwards ."

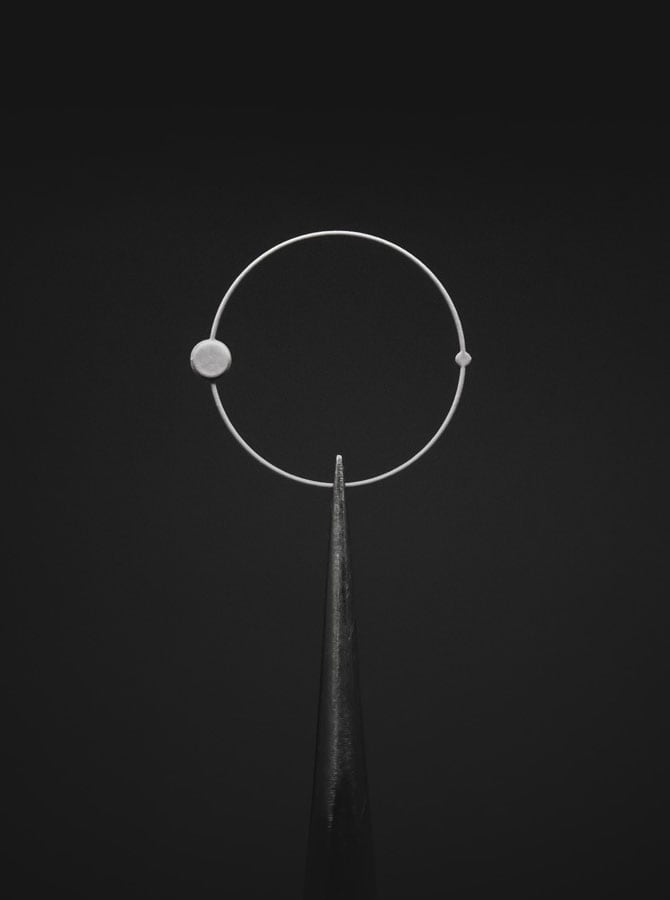

Fencing is a precision, almost choreographic sport. It's hard to imagine how a top-level fencer feels time during an action. Does it slow down, speed up, or dilute? There seems to be a fascinating temporal paradox in this sport. A touch is made in hundredths of a second, but its internal perception can last an eternity. " The goal is to perform the right action at the right time, having put in place the strategies to destabilize the opponent. During the action, everything happens very quickly. But around it, it's as if time expands. I feel more intensely the before and after of a touch, " explains Alex. He calls this sensation "flow," which he describes as a feeling of levitation, when the body and mind become one. A raw, suspended moment, which precedes or follows an immediate sequence: literally going back to the attack. We can't afford to dwell on things; we must always anticipate. " If you think about the previous key, you're dead, because you're already behind on the next one ."

In fencing, the "right" move is not enough. What matters is the right move at the right time. " Perfect timing exists. It's not the most technically beautiful move that hits the mark, it's the one that appears at the exact moment ." And this "exact moment" is not innate or given; it is built through repetition, training, and the construction of an incalculable number of possible scenarios. It's about creating and adopting a body language that will recognize the right moment, the one when the opponent will open a breach. Alex Fava speaks of "starting on time" in fencer's language.

In high-level sport, time is both partner and adversary. It builds, but also destroys. It offers opportunities, only to sometimes take them back just as quickly. " Once again, I didn't know how long my career would last. I set myself short- and medium-term goals, never too long-term. The Olympic Games? Yes, a dream. But in reality, you count competitions, seasons, and days of training before dreaming ." The hardest part isn't shining once, but being consistent enough to stay in the game and the competition. Then the younger players arrive on the scene, the body tires, and even the desire erodes. " What I knew how to do best was fencing. But there came a point when I felt I couldn't go back for four years ." This lucidity is also a form of wisdom, the refusal to hang on too long and the choice not to become "bitter," as he himself puts it.

Alex Fava has always known and wanted to maintain a balance between his life as an athlete and everything else. Even if his schedule has always been built around fencing, it's all he's ever done. He talks about "multi-time": business time (he works at BRED), training time, social time, family time, and romantic time. These compartments are sometimes watertight and porous, but necessary, even vital. " It's tiring to keep going, but for me, it was a lifesaver ," he says, recalling evenings with friends, post-training card games, all those moments that allow him to breathe and release the extreme pressure imposed by the sport. Because high-level competition is a dictatorship that requires a planned, rhythmic, and ultra-controlled life. " From September to July, you know every day exactly what you're going to do for eleven months. Everything is planned. Which is both comfortable... but sometimes stifling ."

Today, Alex Fava is no longer a fencer. He is the coach of the French under-20 team and works at BRED. And above all, he is relearning how to live without sporting deadlines. Finding yourself with free time can seem dizzying at first. " My schedule is no longer punctuated by training camps, practices, and competitions. It's a different way of managing time and a different relationship with it. You have to learn to set other goals. In any case, I'm no longer constrained, or at least much less so! "

Stopwatches and time measured to the hundredth of a second are over for Alex. His watch is now a companion, a piece of jewelry. " I still look at the time, but now I want time to pass more slowly. And I think that happens... when you start learning new things again and setting new life goals, " he says. Perhaps it's in this slow but necessary reconquest and reappropriation of time, or rather of a new time as a new era, that lies the real challenge for the athlete in transition. It's about not remaining attached to yesterday's adrenaline or chasing a glorious past, but about finding a new rhythm, and why not, a new way of savoring the present. One page turns to open another. Alex Fava no longer competes on the fencing pistes, but he continues to have a good time there alongside the young people he coaches. Perhaps it's in this passing of the baton that time finally becomes an ally...